In a Nutshell:

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is commonly used in laundry and dishwasher detergent pods and sheets. It’s the “plastic-y” part that holds the pod or sheet together (until it comes into contact with water, when it dissolves).

- Even though pods and sheets are used by many ‘eco-friendly’ detergent brands, PVA is a kind of plastic (nicknamed liquid plastic).

- This leads to the question of whether or not detergent pods are contributing to microplastic waste and whether they are harmful to the environment (and humans).

- Even though it appears that PVA technically can break down entirely, it’s not clear that it actually does biodegrade in real-world circumstances.

- Unfortunately, very little research has been done on the actual impact of the PVA used in detergent pods. We need more (non-industry-funded) studies to determine whether PVA is safe for humans, animals, and the whole environment. With the info we currently have available, one could conclude that PVA detergent pods are, in fact, contributing to our plastic pollution problem.

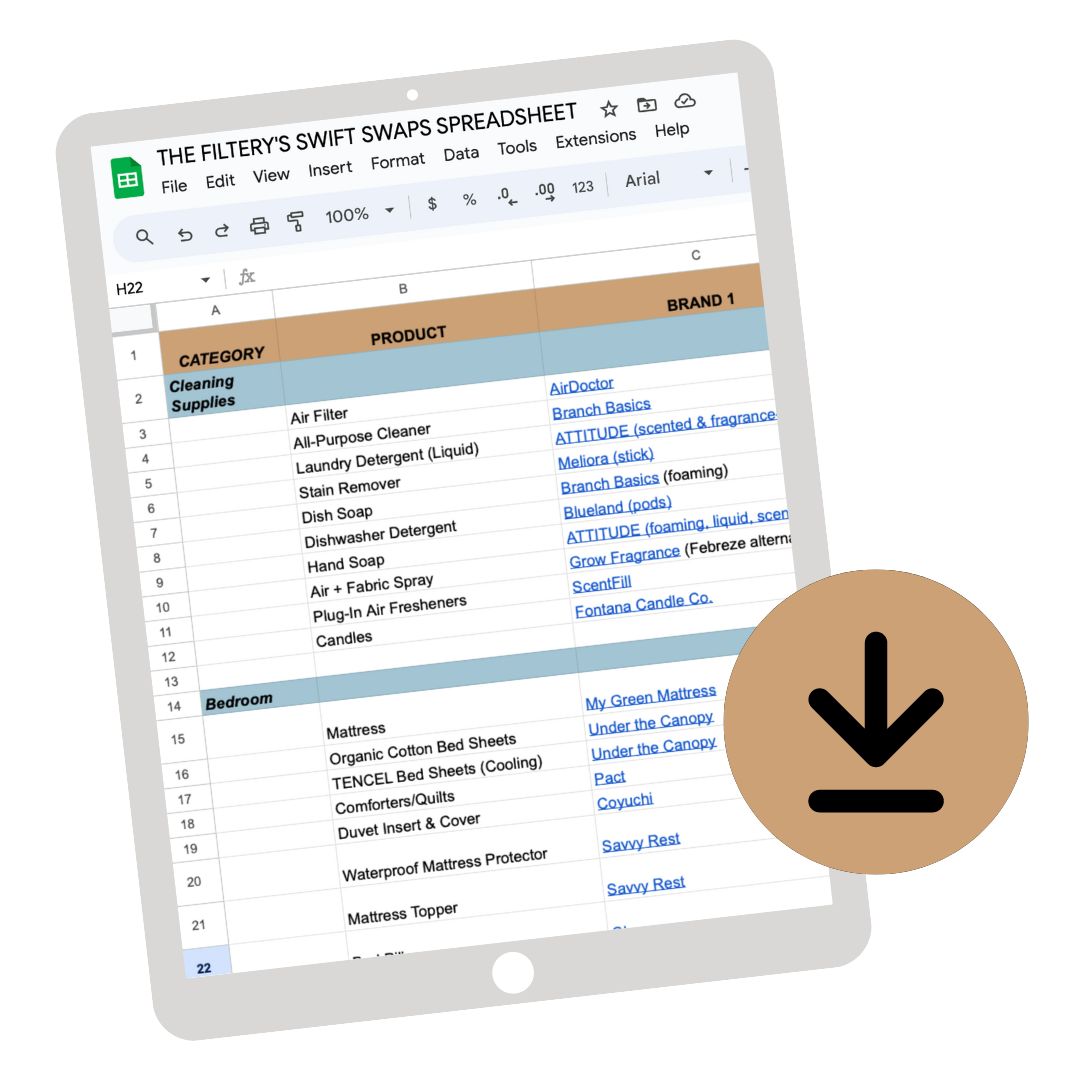

- If you want to skip the PVA detergent pods, we’ve listed several alternative options below. You can either purchase “tablets” (which are basically pressed powder and the closest thing to pods), concentrated liquid detergent, or regular powdered detergent.

When it comes to non-toxic and eco-friendly laundry products, you are so over bulky liquid detergents in heavy plastic containers. Not only are they heavy and take up a lot of space, but they also bear a heavy carbon footprint for being mostly water inside a lot of plastic.

Trendy detergent pods—along with sheets or strips—certainly come with a lot less packaging waste. Some even come in cardboard envelopes. They appear to be the perfect green solution. But are they?

In all of the detergent pods, sheets, and strips I’ve seen, there’s an ingredient that seems harmless: polyvinyl alcohol, or PVA. It’s the “plastic-y” part of the pod or sheet that holds the whole thing together.

Because of the fact that it’s in virtually any cleaning pod meant to dissolve in water inside a washing machine or dishwasher, you’re led to believe it’s safe and non-toxic. But is it?

In this article, I’m examining the facts—and unanswered questions—about PVA. Some of the issues we explore include:

- Does PVA biodegrade completely? (And if so, how long does it take, and under what circumstances?)

- Does PVA decompose into micro- or nanoplastics?

- Is PVA toxic to humans, animals, or the environment?

- Is PVA safe for appliances, plumbing, and septic systems?

- Can PVA-containing detergent pods destroy clothes?

Based on my analysis, you will be in a better position to judge whether detergent products made with PVA are right for you. If you’re looking for eco-friendly detergent products made without PVA, check out my list at the end.

Table of Contents

- What Is PVA? (Polyvinyl Alcohol)

- What Is PVA Used in?

- What Happens to PVA in Grey Water?

- Does PVA Biodegrade Completely in Nature?

- PVA & Microplastics

- Does PVA Decompose into Microplastics?

- How Are Humans Exposed to Microplastics?

- What Are the Health Effects of Microplastics?

- Is PVA Degraded at Wastewater Treatment Plants?

- Do Microbes Use PVA as a Food Source?

- Is PVA Toxic to Aquatic Organisms?

- What are the Breakdown Products of PVA Degradation?

- Laundry Products Without PVA

- Is PVA harmful to plumbing systems or appliances?

- Is PVA harmful to clothes?

- Is PVA plastic?

- Are laundry pods better than liquid?

- Key Takeaways Re: PVA in Detergent Pods

This article contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a commission if you decide to make a purchase.

What Is PVA? (Polyvinyl Alcohol)

Also called PVA, PVOH, and PVAL (or its many trade names including Polyviol, Alcotex, Covol, Gelvatol, Lemol, Mowiol, Mowiflex, and Rhodoviol), polyvinyl alcohol is a form of plastic (synthetic polymer or resin).

But it’s not like typical plastics that are hard and float on water. PVA dissolves in water, giving it the nickname liquid plastic.

Polyvinyl alcohol is made in the lab from polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) and water in a chemical reaction involving ethanol. You may already be familiar with polyvinyl acetate used in:

- Elmer’s Glue

- Chewing gum

- Adhesives in book bindings, wallpaper, and envelopes

Polyvinyl acetate is made in the lab from acetic acid (the major ingredient in vinegar) and ethylene, a fossil fuel derivative.

What Is PVA Used in?

Like the chemical it’s made from, polyvinyl alcohol has many common uses. You may find it in:

- Adhesives

- Paints

- Textiles

- Food packaging

- Paper coatings

- Pharmaceuticals

- Contact lenses

- Vascular stents

- Cartilage replacements

- 3D printing

- Household sponges

One of its more recent uses is as the flexible film encasing liquids in dishwasher or washing machine detergent pods or strips. The dissolvable coating of these pods is made up of PVA and other substances such as glycerin. Research shows the amount of PVA in pods (by weight) is between 65% to 99% of the total outer coating weight.

Did you ever consider what happens to PVA after it leaves your home in grey water?

What Happens to PVA in Grey Water?

So far, there is only one peer-reviewed study, partially funded (50%) by Blueland, on the fate of PVA once it leaves your dishwasher or washing machine. Published in 2021, Rolsky and Kelkar examined the fate of PVA in the United States after it leaves your home in dish and laundry grey water.

Through survey and model results, they estimated that in the United States:

- Roughly 15 billion laundry pods and 12 billion dish pods are used every year by 126 million households

- 17,200 ± 5000 metric ton units per year (mtu/yr) of PVA are used

- 10,500 ± 3000 mtu/yr of PVA enter wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs).

- Approximately 77% of PVA leaves WWTPs undegraded

- Several states with the highest PVA emissions, either untreated or via WWTP effluent, border the Pacific or Atlantic Oceans. So, rapid release of PVA into marine environments is possible.

- 8100 ± 2400 mtu/yr of PVA remains untreated every year.

Based on their analysis of peer-reviewed studies concerning wastewater treatment plant contaminants and data incorporation into their model, the researchers concluded that roughly 61% of PVA entered the environment as sludge. Approximately 16% of PVA reached the environment dissolved in water, likely as wastewater irrigation or runoff.

Here is a flow diagram summarizing the fate of PVA after it leaves your home:

Ultimately, PVA in sludge (biosolids) ends up in these three destinations:

- 50–60% is applied to agricultural lands

- 20% is incinerated

- 17% is landfilled

What is not yet precisely known is how much PVA:

- Is taken up by animals and plants eaten by humans

- Becomes airborne

- Enters leachate or groundwater

Does PVA Biodegrade Completely in Nature?

It is not known if PVA biodegrades completely in nature. If it does, microbes likely play a major role in its degradation.

According to research published in 2009, there are several species of microorganisms that degrade polyvinyl alcohol, at least partially, under certain environmental conditions. The degree of breakdown depends on many factors. One of them relates to how much of the polyvinyl acetate had successfully reacted with water during PVA formation.

The reason it’s important is that the mechanism of some of the microbes degrading PVA involves the arrangement of certain chemical groups on the PVA polymer. When these groupings are not present in high enough quantity, biodegradation would be incomplete.

The chemical reaction used to form PVA commonly used in detergent pods is roughly 88% completed.

It’s still unclear whether this type of PVA would degrade completely under real-world conditions. All of the bacterial species known readily to degrade PVA are not frequently found at wastewater treatment plants or even common in the environment. Nor are the conditions necessary for PVA to completely degrade found in all natural ecosystems.

PVA & Microplastics

Does PVA Decompose into Microplastics?

The term microplastics is commonly understood to apply to tiny bits of hard plastic 5 mm or less in diameter. However, this definition was proposed before detergent pods made with liquid (soft) plastic hit the market in full force.

So maybe it’s time to rethink the term microplastics to include all types of plastic, including PVA. But rather than get mired in a semantic disagreement, we can refer to PVA in the environment as an unwanted liquid plastic material.

How Are Humans Exposed to Microplastics?

Humans are exposed to microplastics primarily through inhalation or digestion. Since microplastics are known to enter land ecosystems 4-23 times more than oceans, ingestion through food and water are of greatest concern. Scientists estimated in 2019 that humans receive per year:

- 39,000 to 52,000 microplastic particles via foods and beverages (Increase it by 90,000 more if you drink bottled water only.)

- 35,000 to 69,000 microplastic particles through inhalation

In their article, the investigators noted that their numbers are likely underestimations.

Some of the primary ways microplastics are transported to land are by sludge deposition or by wastewater irrigation. In fact, a UK study from 2022 revealed the equivalent of more than 22,000 credit cards’ worth of plastic is deposited on land every month in that country through sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants.

Both sludge deposition and wastewater irrigation could result in the addition of PVA and its breakdown products to agricultural areas leading to their uptake into plants and eventual consumption by humans.

A 2022 study showed that polyethylene (polymer of ethylene) was one of the most common plastic chemicals in human blood samples. As noted above, ethylene is a breakdown product of PVA.

What Are the Health Effects of Microplastics?

The effects of microplastics on human health are just beginning to be discovered. So far, preliminary findings in lab animals and in human cell cultures are not positive. The adverse health outcomes from microplastics include:

- Gut microbiome disruption leading to inflammation (from polyethylene exposure)

- Poor sperm quality and reduced testosterone (from polystyrene exposure)

- Learning and memory deficits (from polystyrene exposure)

- Increased formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), markers for oxidative stress leading to inflammation (in human kidney and liver cells)

Is PVA Degraded at Wastewater Treatment Plants?

Research on wastewater treatment plants has found that PVA is optimally degraded when there are more microbes present than typically used in WWTPs. There is also a lag time of several weeks necessary for microbes to become adapted to PVA and be able to degrade it.

Further complicating the issue is that a heavy influx of textile industry wastewater is required for the adaptation process to be successful. But there are no textile plants generating such wastewater all over the country.

Typically, the time wastewater spends in treatment plants is hours or days—not sufficient for the adaptation process to occur fully. This means PVA would not be completely degraded in traditional WWTPs.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USCDC), chlorination is the most common way to treat wastewater. Research shows that PVA is only minimally affected by this treatment method.

Similarly, sand filtration is used in WWTPs to remove pharmaceuticals. Although PVA removal by sand filtration has not been investigated, substances like PVA are not filtered well by sand. So, we may assume PVA would not be, either.

Sludge (biosolids) is often treated in WWTPs by microbes under anaerobic (no oxygen) conditions. In a 2009 study, PVA of various weights was subject to this treatment. Breakdown was very low (13%) after 25 days. After 150 days, it increased to 37%-50% with larger-sized PVA undergoing more degradation. A 2013 study using a PVA-glycerin blend showed only 4% degradation in 30 days.

Peer-reviewed studies, not industry-funded lab experiments with PVA-adapted microbes, are needed before we can draw any definitive conclusions about the biodegradability of PVA in wastewater treatment plants or in real-world environments.

Do Microbes Use PVA as a Food Source?

Whether PVA biodegrades is one question. Another pertinent issue is whether microbes can use (assimilate) PVA or its breakdown products for living. In other words, are microbes able to use the carbon-containing degradation products as food sources? Not all microbes can, in which case the degradation products will remain in the environment. Their potential toxicity would need to be assessed in this case.

Microbes have been functioning members of ecosystems for billions of years, assimilating carbon and other elements for growth and reproduction. Synthetic, fossil fuel-derived chemicals are relatively new additions to the environment. Wild-type microbes in the real world—not lab-engineered strains—may not have the necessary biochemical machinery to be able to degrade and assimilate synthetics like PVA. Further research is required before a definitive conclusion on PVA’s degradability and assimilation by microbes can be reached.

Is PVA Toxic to Aquatic Organisms?

A 2022 study by Nigro et al showed that PVA is non-toxic to two species of aquatic organisms. However, the result has not been corroborated by other investigators, so we cannot say with great confidence that this result is definitive. Before any result becomes accepted as true, several different researchers need to replicate the experiments and arrive at the same conclusion. Also, testing PVA in the presence of other marine organisms is necessary before a general claim of non-toxicity toward aquatic species can be made.

Although PVA is thought to be non-toxic by some people, it displays strong surface activity on water where it produces large amounts of foam. This characteristic suggests PVA would reduce oxygen levels in the water, compromising the ability of aquatic animals to live there. At this point, research on the fate of PVA in the environment is sorely lacking.

Additionally, microplastics often attract other contaminants—including endocrine disruptors and heavy metals—to physically or chemically bind to them. In this manner, they transport chemicals and widen the range where they can cause damage to organisms and ecosystems.

A 2015 study using PVA to remove the heavy metal cadmium from the environment because of its tendency to bind to it suggests PVA from wastewater treatment plants used as sludge or irrigation water could transport heavy metals. PVA can also leach into groundwater. Further research on how PVA behaves in the environment is needed.

What are the Breakdown Products of PVA Degradation?

According to Dr. Charles Rolsky, fossil fuel-derived “ethylene can be a byproduct of PVA degradation.” Ethylene is one of the major chemicals used to make many types of plastics. It is also a greenhouse gas, contributing to global heating and the climate crisis.

Scientists are just beginning to investigate the contribution of ethylene emitted from plastic pollution to global heating. While plastics strewn on land send more ethylene into the atmosphere compared to soluble plastic, there is still some ethylene emanating from waterborne plastic. So, both biosolids and liquid water containing PVA contribute carbon emissions. As emissions increase worldwide accelerating the climate crisis, we can reduce them by eliminating plastic use.

If ethylene-containing biosolids are used as fertilizer on crops, then ethylene created from PVA degradation would not only contribute to the climate crisis. It would also be a potential biohazard contaminating food intended for human consumption.

Another breakdown product of PVA could be carbon dioxide (CO2), a major greenhouse gas. If carbon dioxide remains dissolved in water, it hastens acidification which is detrimental to many aquatic plants and animals. Whether in water or air, carbon dioxide traps heat, raising the temperature of both. In water, CO2 causes oxygen to be depleted. Neither temperature elevation or oxygen reduction is conducive to life for most organisms.

Laundry Products Without PVA

Most detergent pods use PVA, with some exceptions. Some “pods” are more like “tablets” that are basically made by pressing powder together rather than being held together by PVA. For example, Blueland’s laundry tablets and Branch Basics’ dishwasher tablets are both PVA-free.

You can usually tell the difference by looking at them. Here you can the difference between the PVA pods and the PVA-free tablets:

Manufacturers of PVA detergent pods claim the measured quantity of detergent in each pod simplifies laundry duty. Critics say it’s too much detergent for the recommended load size.

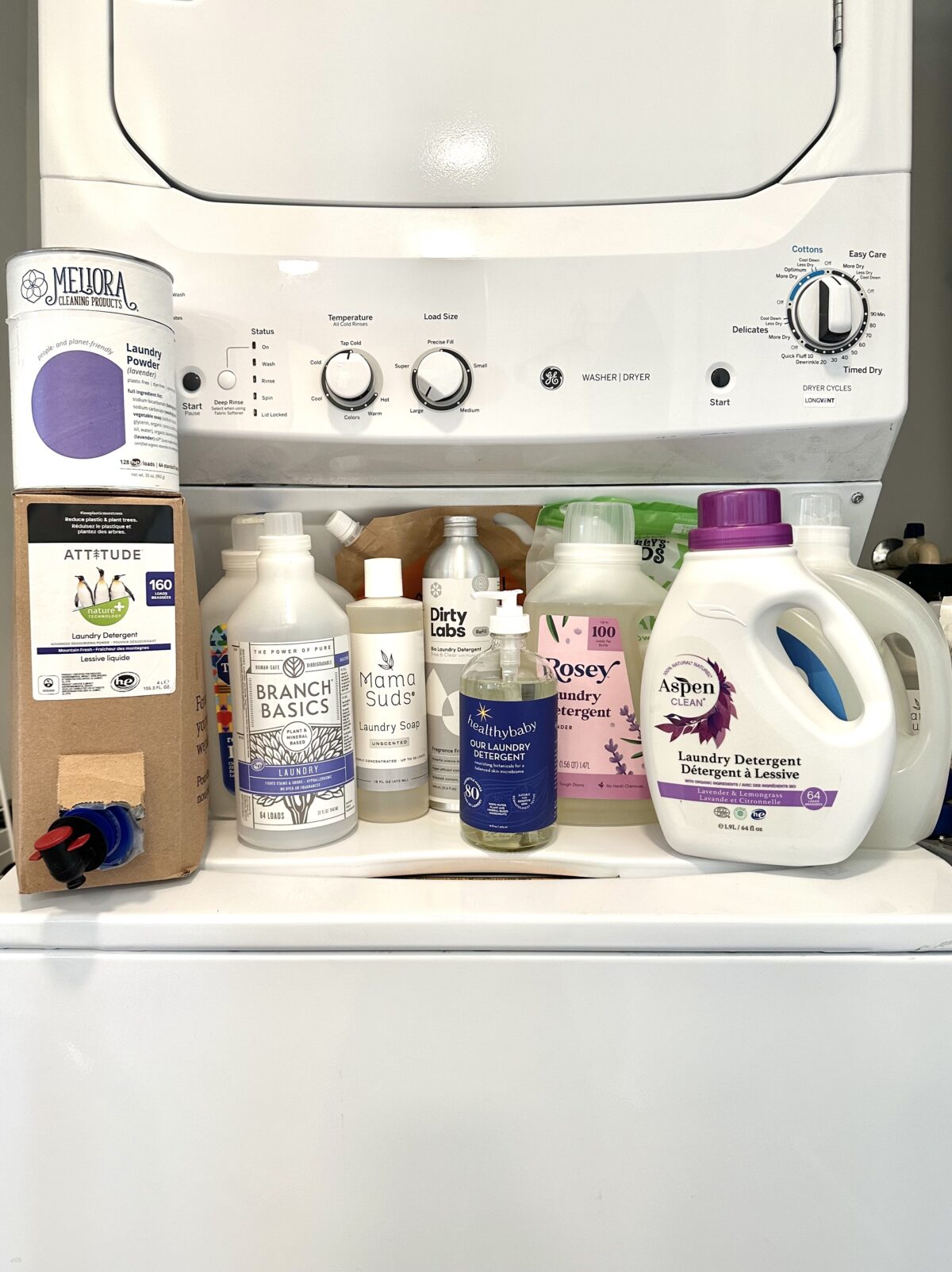

To avoid this problem, you may wish to purchase a bulk laundry product that is PVA-free. Dirty Labs super concentrated liquid laundry detergent (Free & Clear) in metal bottles from which you pour out a desired quantity allows you to use as little as possible while still getting clothes clean. Dirty Labs BioEnzyme Laundry Booster is a green product that complements the brand’s detergent.

Meliora carries effective, plastic-free laundry detergent that comes in regular powdered form.

Again, powdered detergents in tablet form from Blueland is another eco-friendly option without PVA. Branch Basics also carries PVA-free dishwasher detergent tablets and concentrated liquid laundry detergent.

For more non-toxic laundry detergent options, check out our full laundry detergent guide (although not all of these options are plastic-free).

Home

15 Best Natural & Non-Toxic Laundry Detergents (By Category!)

Popular laundry detergent brands have ingredients linked to allergies and even cancer. Here are the best non-toxic laundry detergent brands you can feel safe using in your home.

Is PVA harmful to plumbing systems or appliances?

I have seen online comments from plumbers and appliance repairers suggesting that undissolved polyvinyl alcohol can wreak havoc in the internal mechanism of systems and appliances. They recommend that you not use laundry products containing PVA. Doing so could result in an expensive repair or replacement.

Is PVA harmful to clothes?

I have seen online comments from detergent pod users describing how a plastic film believed to be PVA sticks to their clothes. It is impossible to remove it, resulting in the need to purchase replacements. If you do use detergent pods, make sure to follow the directions.

Is PVA plastic?

Yes, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a type of plastic. Since it dissolves in water, it’s different than what typically comes to mind when we think of plastic. That’s why it’s earned the nickname “liquid plastic.”

Are laundry pods better than liquid?

There are definitely pros and cons to both pods and liquid detergent; one is not necessarily better than the other. For many consumers, the primary draw of laundry pods is that they’re quicker and easier to use than liquid detergent—you just grab a pod and pop it in the washing machine. They also tend to be less bulky than liquid. That said, the PVA in the pods could be leaching microplastics into our environment. Until we have more conclusive research, you’ll have to decide for yourself whether or not you think pods are better than liquid.

Key Takeaways Re: PVA in Detergent Pods

At the present time, there is no conclusive evidence that PVA is non-toxic and safe for the environment. However, this is an active area of research and the final word is not yet in.

There are certain microbes which are known to eat PVA. However, a study revealed that 75 percent of PVA from detergent pods remained intact after passing through conventional wastewater treatment plants. Many of these public utilities use microorganisms to biodegrade pollutants before wastewater is released into the environment.

Even if microorganisms completely broke down PVA into the simple elements of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen in the lab, they may not do so under real-world conditions. In fact, fossil fuel-derived ethylene, the parent compound of PVAc used to make PVA, is a known degradation product in the environment.

The implications of having ethylene in the soil for agriculture, and, thus, in the food supply, are unknown at this time. So, until more scientific studies are conducted on PVA in the environment, I conclude that PVA contributes to the plastic pollution problem. We should not be intentionally adding it to the environment via detergent pods if alternatives exist.

For people looking for an alternative to PVA-containing detergent pods, there are a few products on the market that do not contain PVA. ‘We have listed them in this article. I’ve listed them above!